This post is about three years late, but I’m catching up.

Combat robots like Battlebots are seeing something of a revival right now.

The ones on the Battlebots show are 250lbs, and cost tens of thousands of dollars – most of that in batteries.

Much more accessibly, there are a bunch of regional competitions, at a variety of weight classes. 3 and 30 pounds are the most popular, as a trade-off between expense, challenge, and excitement (heavier has more of the latter, at the cost of the first two).

Someone local to me was trying to start a one pound league, so I took the opportunity to build one as a way to dip my toes in.

Unlike my previous hacky RC car, the roadmap for the electronics is a lot better defined.

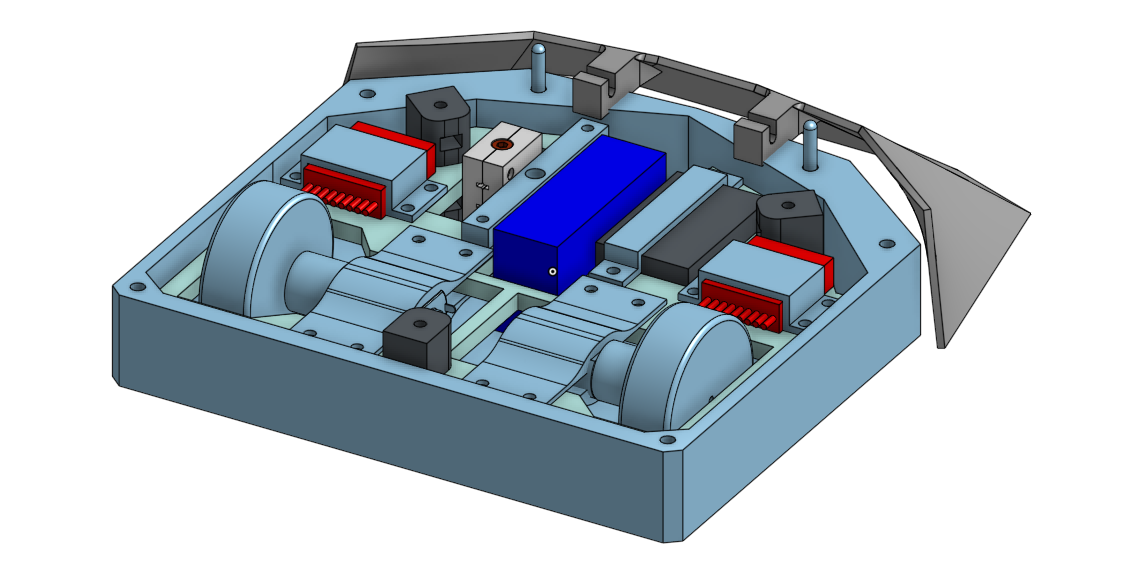

A wedgebot (that is, just a driving platform, no active weapon) consists mostly of these components:

- Wheels

- Wheel motors

- Chassis

- Power switch

- ESC

- Receiver / RX

- Battery

- Transmitter / Controller

All of these are easy commodity parts.

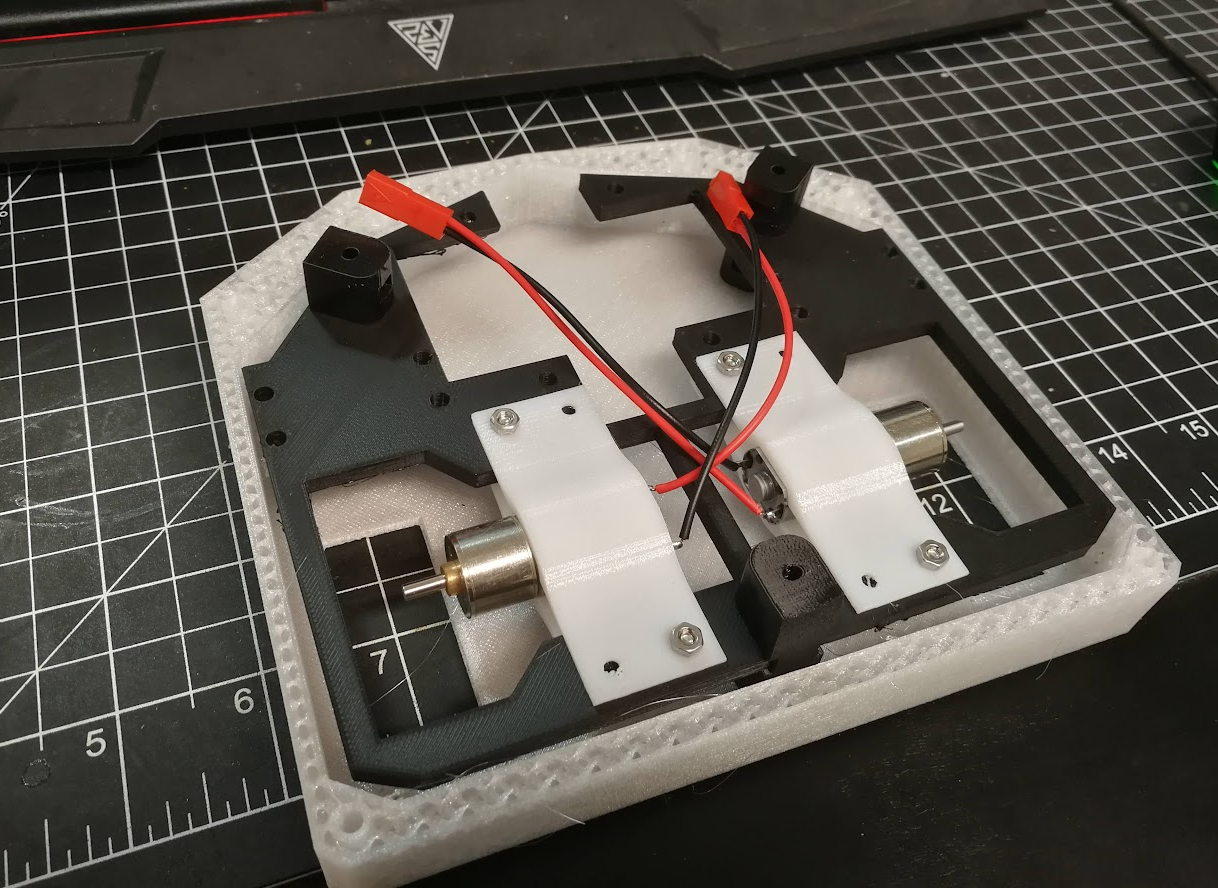

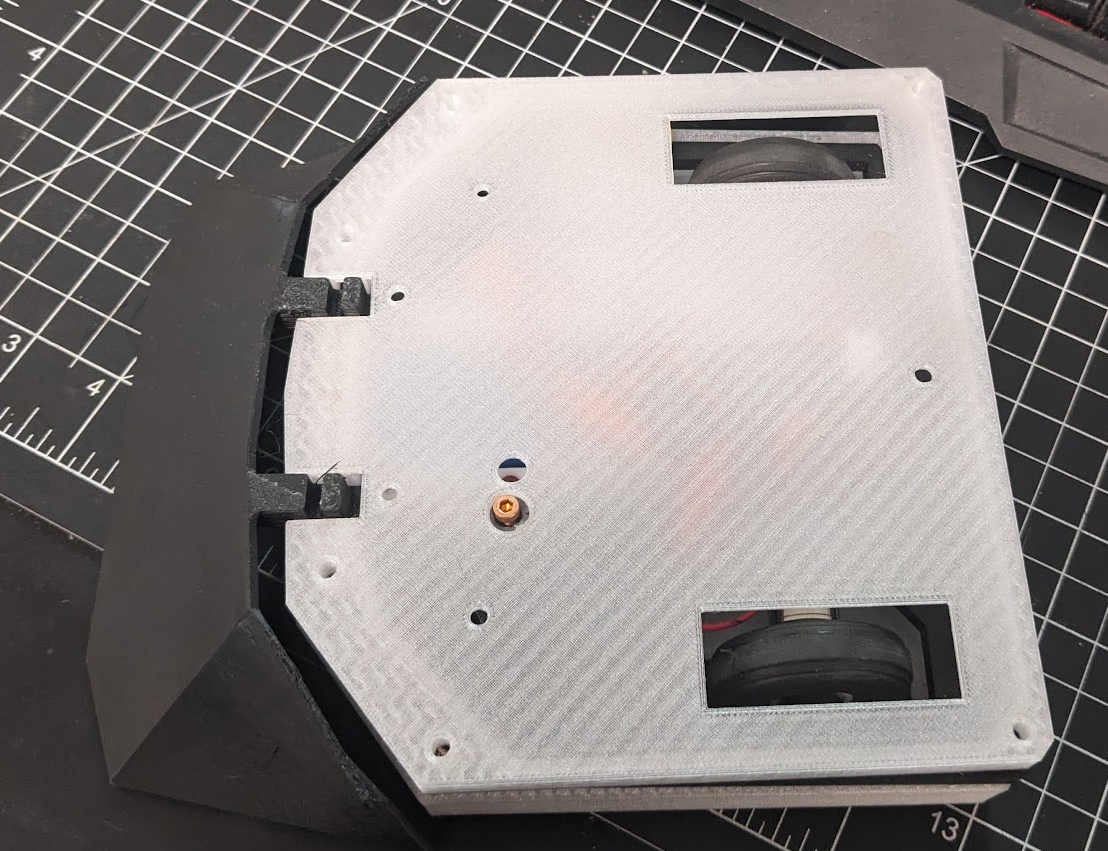

I 3D printed the chassis and then the internal frame to hold everything together – PETG for most of it, and then some soft rubbery TPU shockmounts to attach the internal and external components, ideally kinda cushioning the electronics. Similarly the motors are held on with some thin PETG to allow flex to absorb shocks.

The motors are 800 RPM DC motors. That seemed like a good compromise on speed vs. control with this size of wheel.

The wheels are 45mm rubber/foam wheels.

The ESC is a 5A board, that can take a forward/direction control, and turn it into left/right tank steering. Originally I had an ESC designed in for each motor, but the ones I specced out didn’t work with the tank steering setup. This one nicely controlled both motors, after translating the two data channels into what I needed.

This was critical because my controller is a Spektrum DX3s, which only has forward/back and left/right channels. The controller also came with a compatible receiver.

The battery is a tiny 550mAh thing.

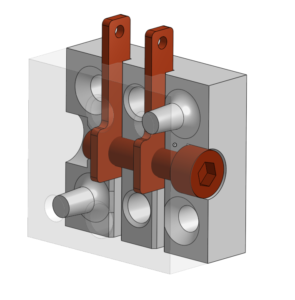

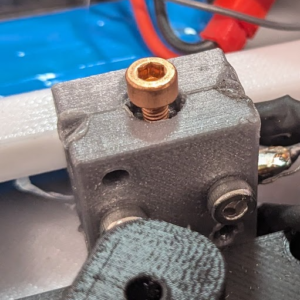

There are two philosophies on power input from the battery. Some people run power from the battery-positive to a pin on a connector, with the rest of the system connected to the connector’s other pin. This allows the whole system to be powered up by plugging in the mating connector with both pins soldered to each other. This is cheap and easy, but it’s pretty common to see the link fly off during fights.

The other solution is a custom power switch that a few industry people sell. It seemed rather expensive for what it is, so I made my own with a copper bolt and copper plate and 3D printed PLA.

Anyway, shortly after I finished it, the prospective event organiser of the 1lb league had to skip town, so this has just been lying in a box since then. That’s a pity, it would be fun to smash it up. I would undoubtedly learn a lot.

It’s pretty zippy.