I bought a used lathe.

It’s a Craftex B1979C, which seems to be nearly identical to a Craftex CX704. Similar to many such mini lathes, actually, with varying swing lengths.

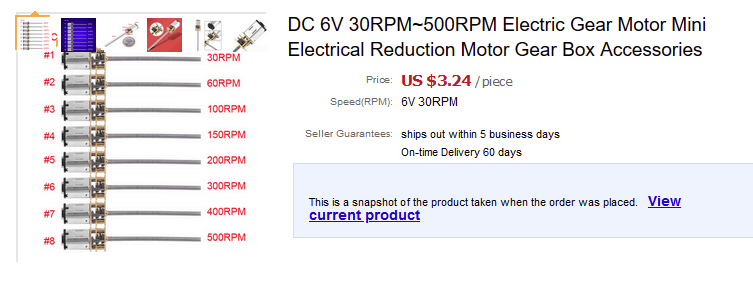

The previous owner explained, a little bit sheepishly, that he tried to cut steel a little too hard, and burned out the AC motor. He replaced it with a hobby BLDC motor and ESC, designed for things like quadcopters.

I played around with that system a little bit, and I didn’t like it.

Annoyingly, he bought a $50 motor and a $50 motor controller, both sensorless versions. For these kinds of motors, you need sensors to start up at low speeds with torque on the motor. That would have cost $60 for the motor and $60 for the motor controller – Not much extra for him, but annoying for me to have to shell out the full amount for both, and then have the old ones as somewhat useless spares.

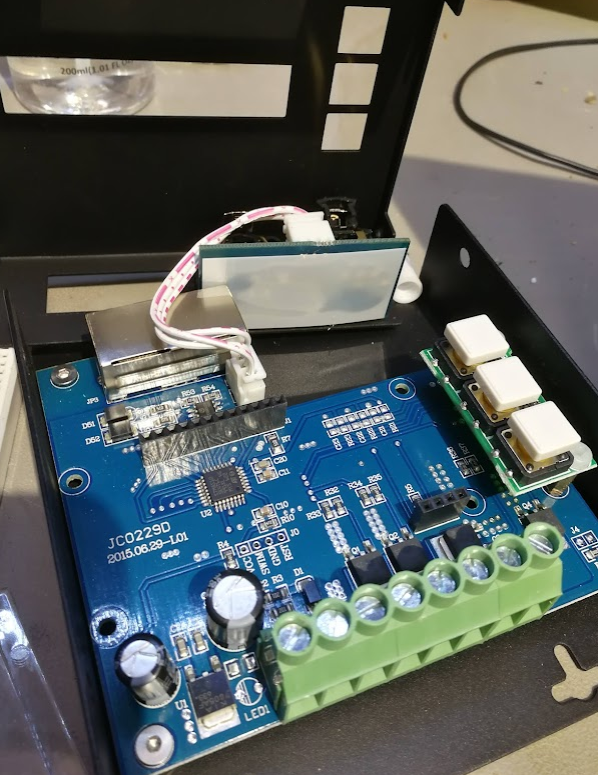

Anyway, instead of going the same route, I chose to get a more sophisticated controller so that I could precisely control parameters, like speed, or acceleration. The options are essentially vESC or ODrive, unless I want to custom build something myself (I do not).

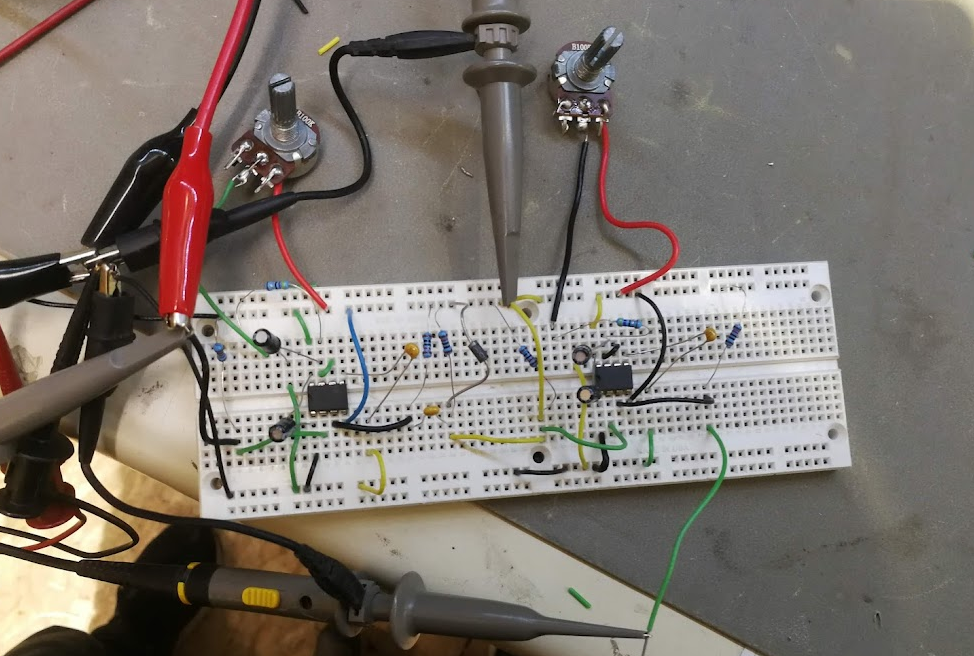

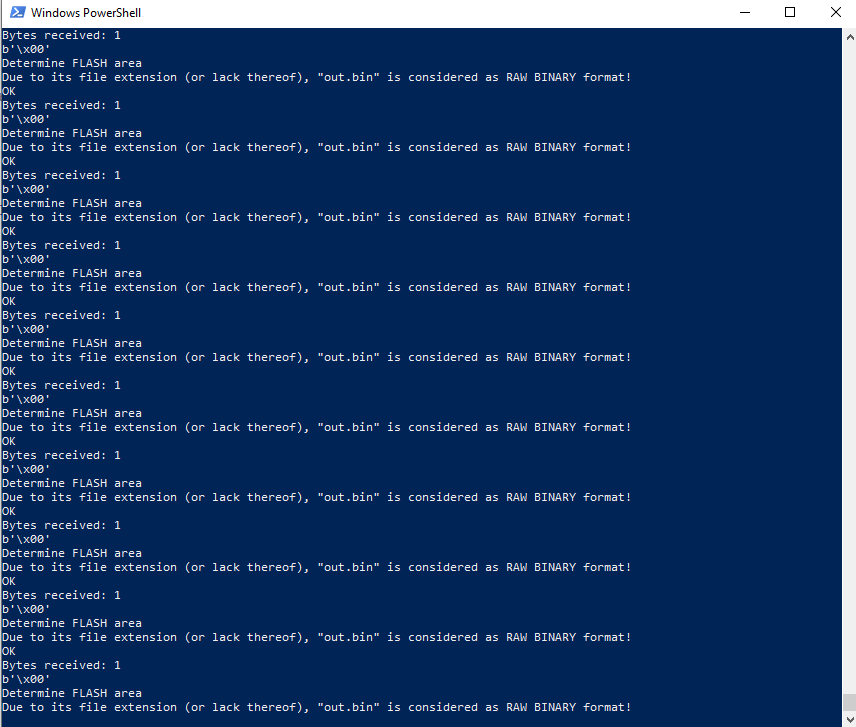

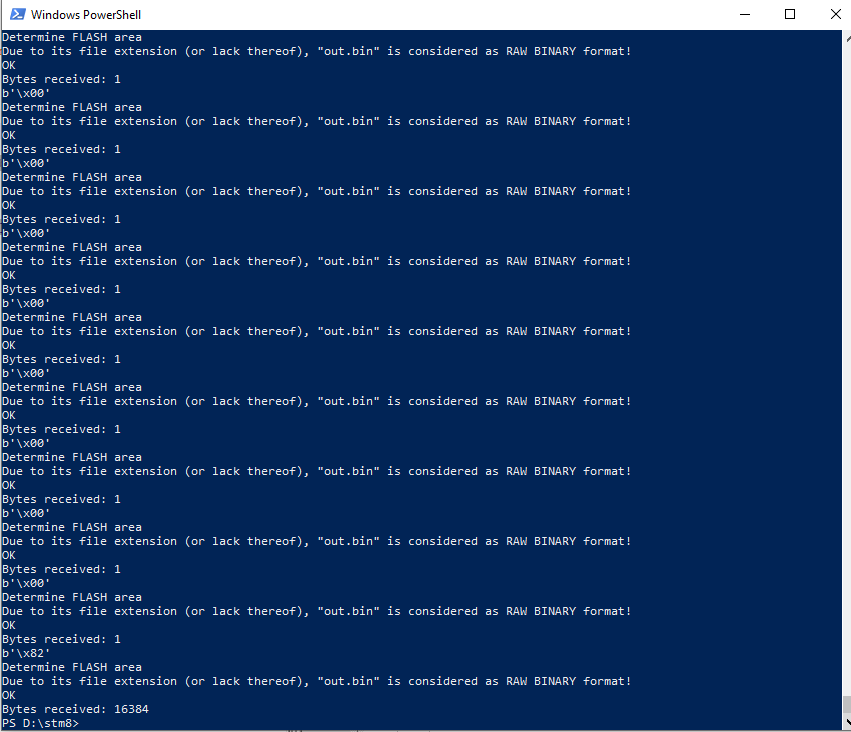

The ODrive, at least on paper, looked a little cooler. Some good communication strategies, lots of control modes, and generic enough to work well for this somewhat strange application. Right after I’d picked mine up, they discontinued support of the V3.6 and went to a closed source model, which rubs me the wrong way. The new version is also more expensive and has a single channel instead of two channels. One of the big issues with the legacy release is that there is a bug in their UART driver – If you send enough malformed packets, like, say, because you have a data line right next to a spinning motor, then the controller eventually stops responding to all UART data. That can be an issue when the packet you want to send is “stop now, immediately”. That definitely hastened my building of a separate e-stop box.

Fortunately, after I wrote a CANBus driver and used that, it’s been reasonably solid. That was just more of a time investment than I wanted to make.

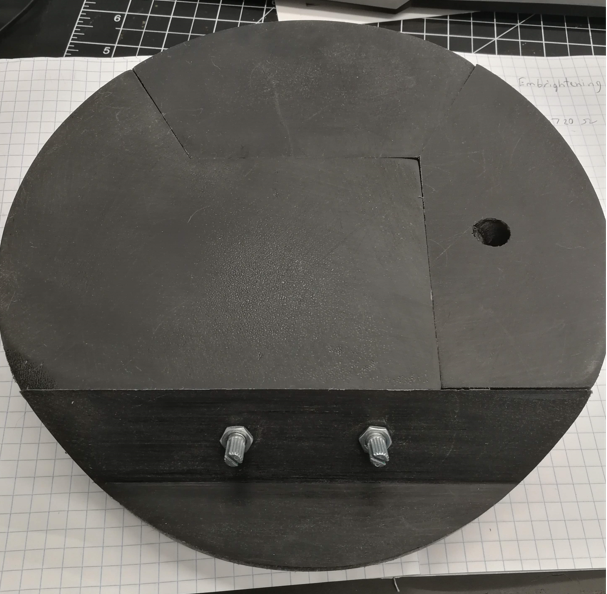

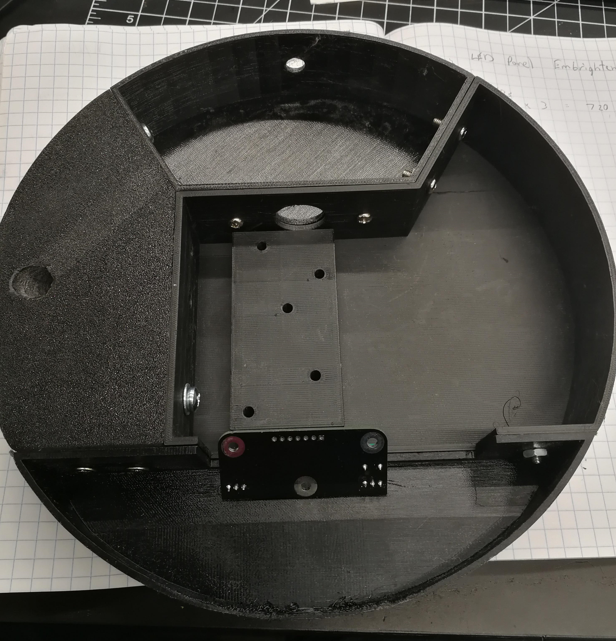

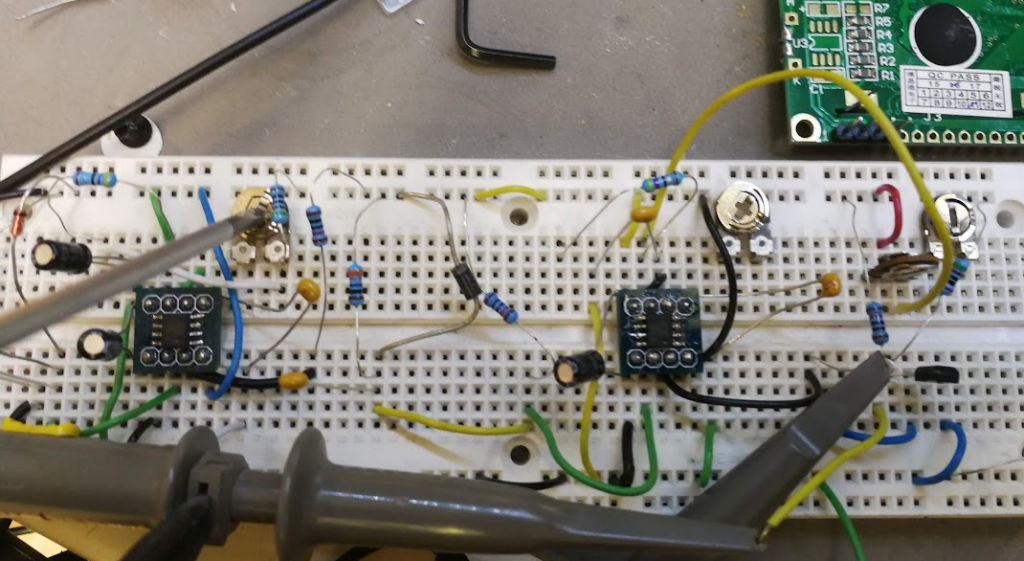

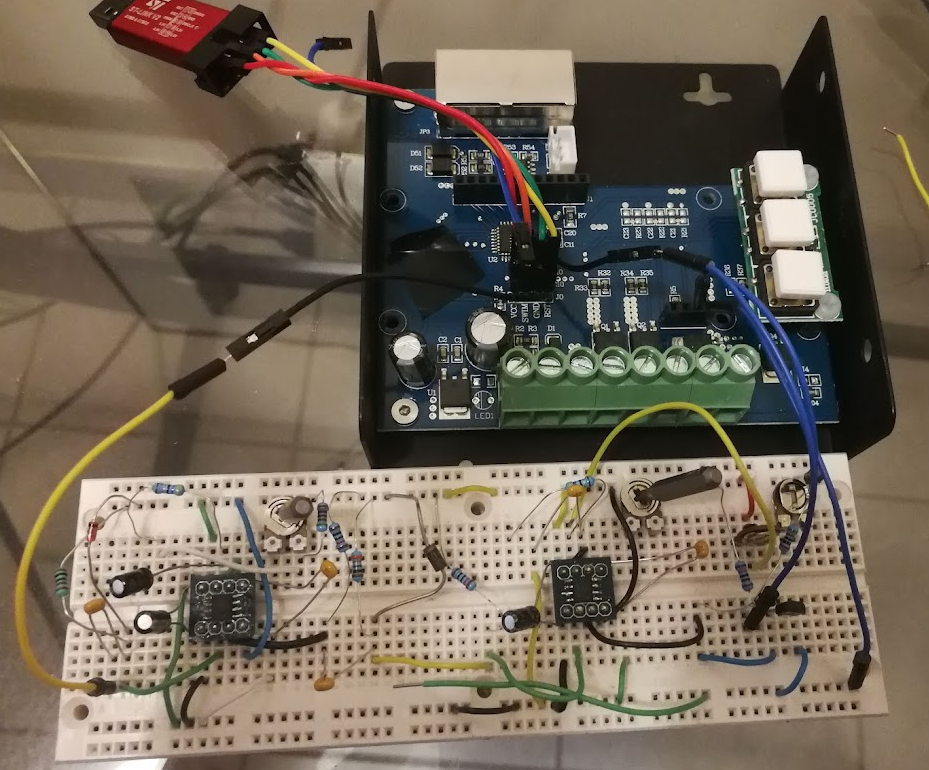

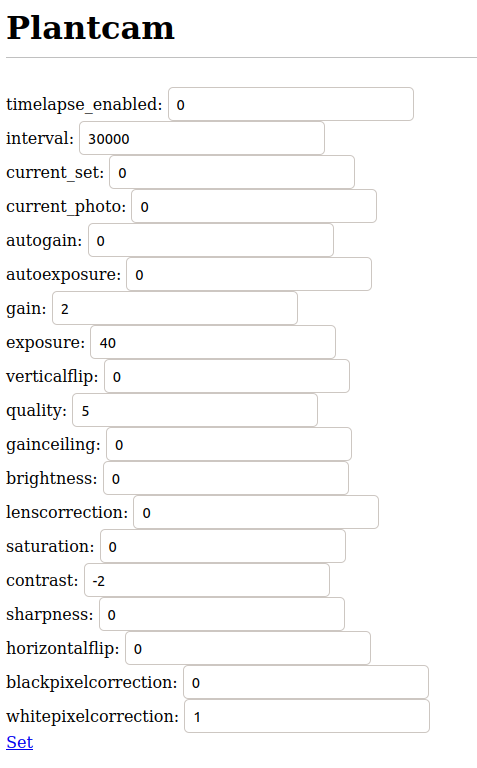

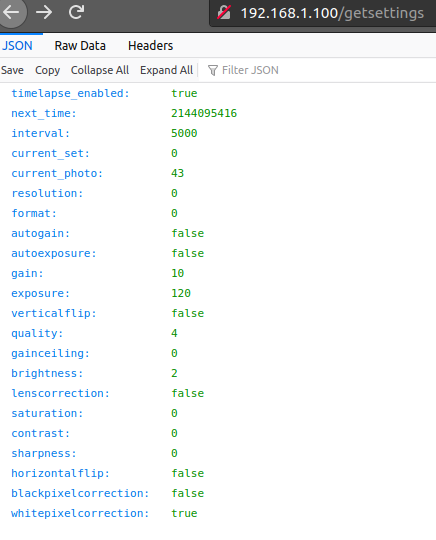

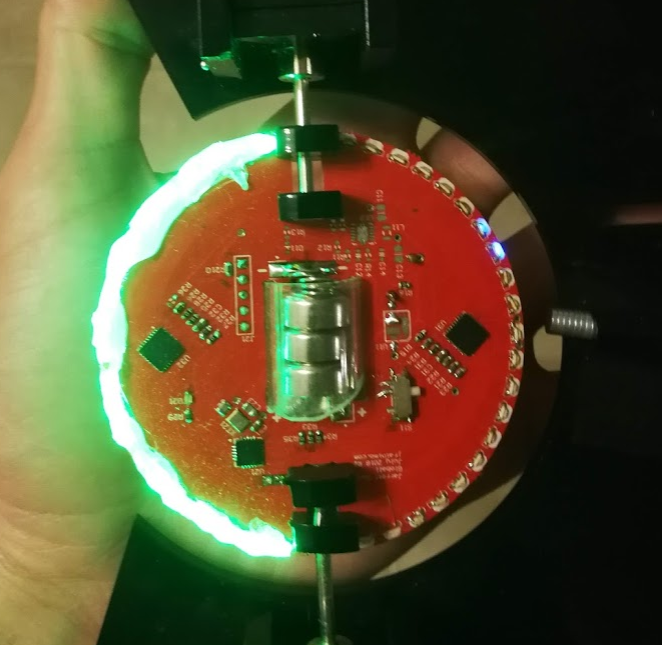

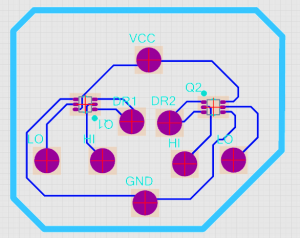

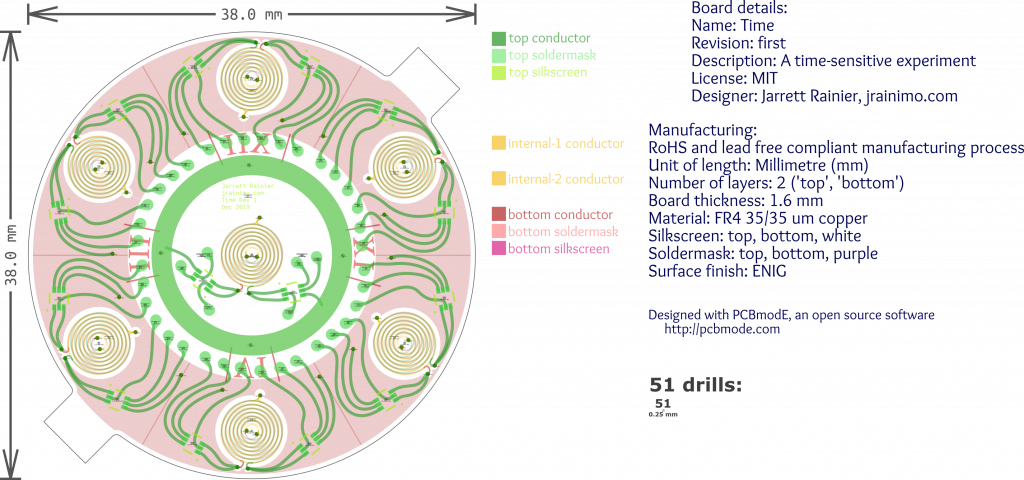

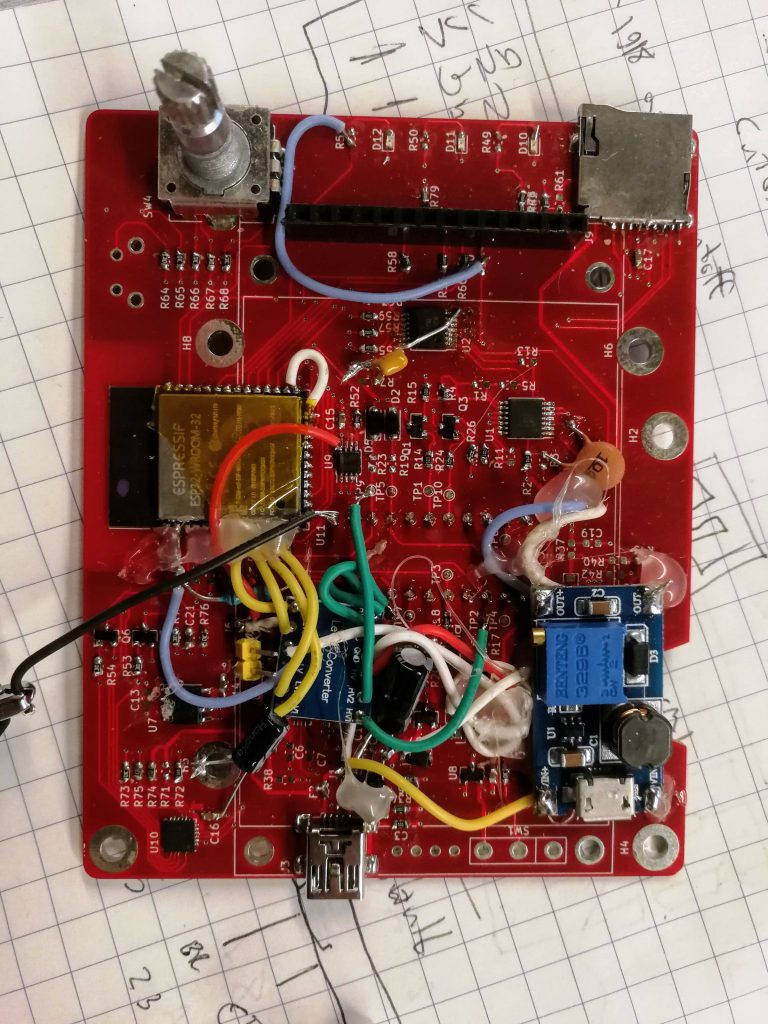

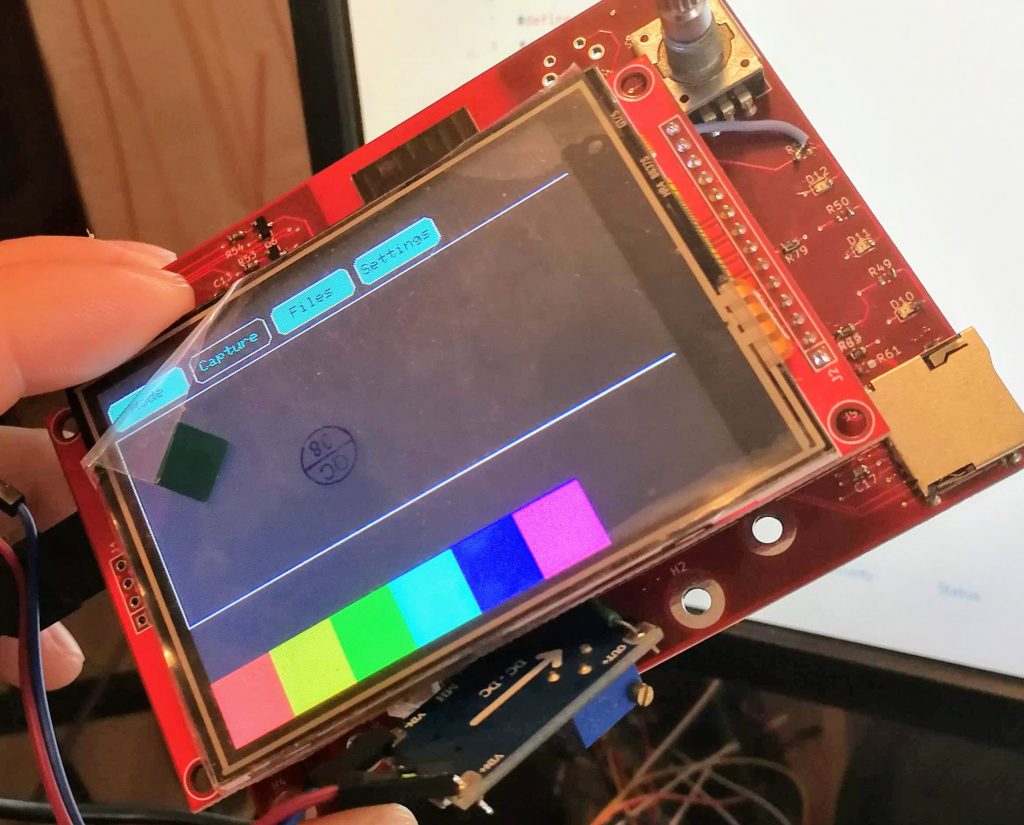

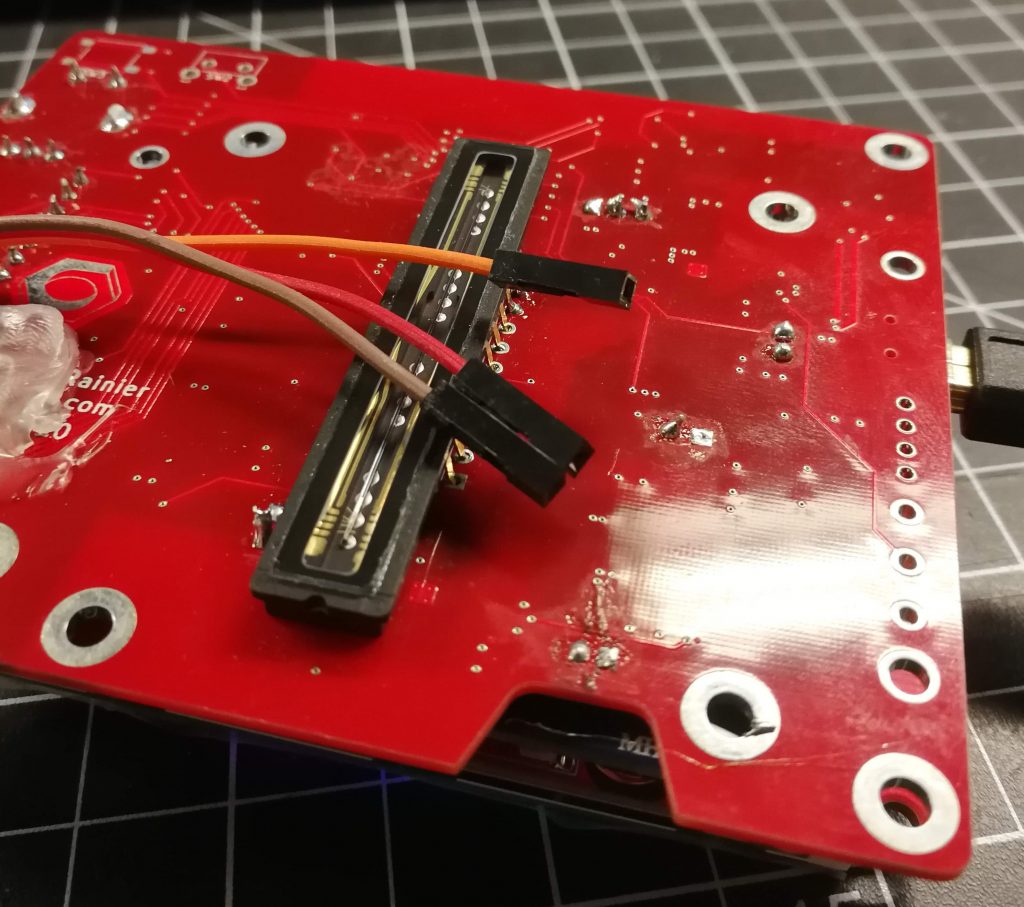

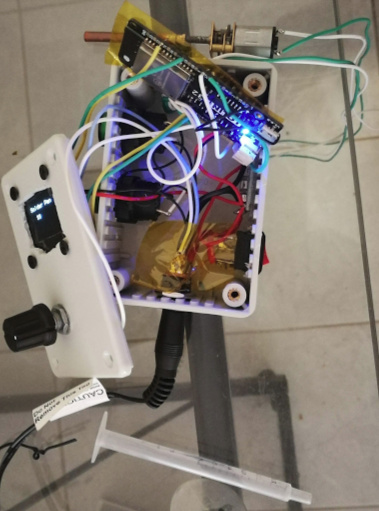

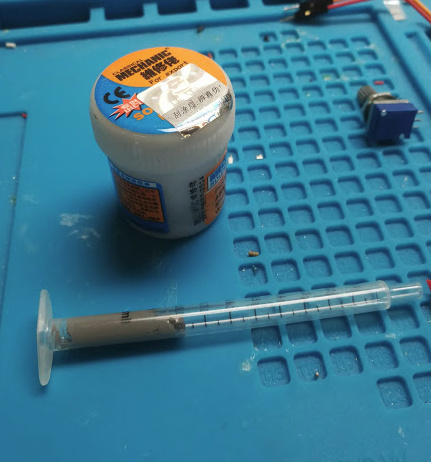

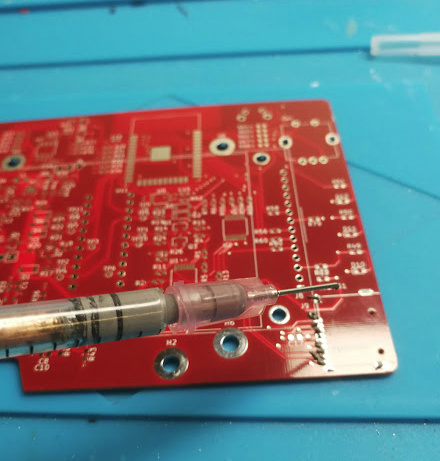

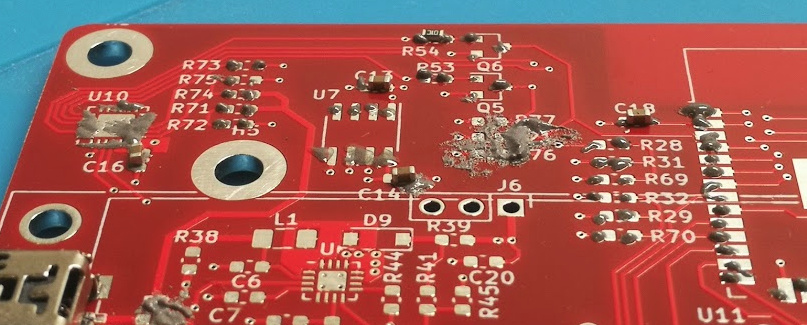

I built a front panel for it as well. It’s a couple simple PCBs holding the switches, OLED, buttons, and a dev board. The advantage of not including everything on a complicated PCB is that I can pop out the dev board to flash it on my bench, before returning it to the lathe. The dev board is an ESP32, which is driving a little OLED screen that shows the target and measured speed, current, forward and backwards directions of the motor controller. The list of features I could add is nigh-infinite, but this is good enough for now. Oh, and I can do software updates over the internet! There is no way this can end badly.

It’s weird how sometimes three sentences can encompass four months’ worth of occasional project time.

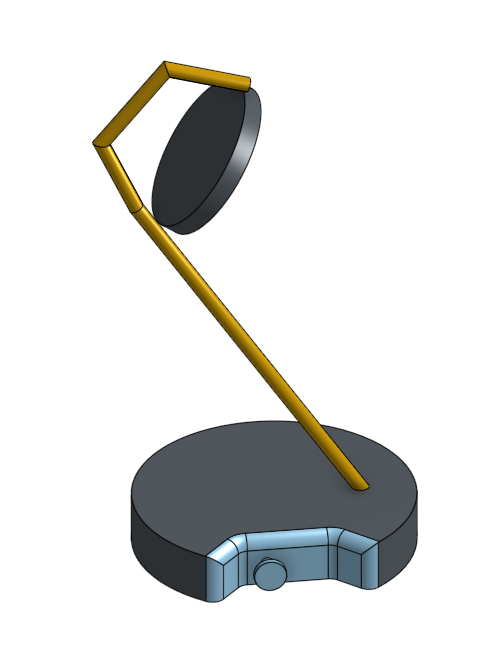

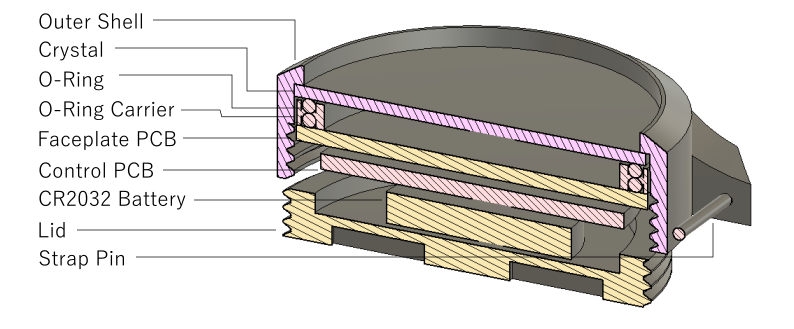

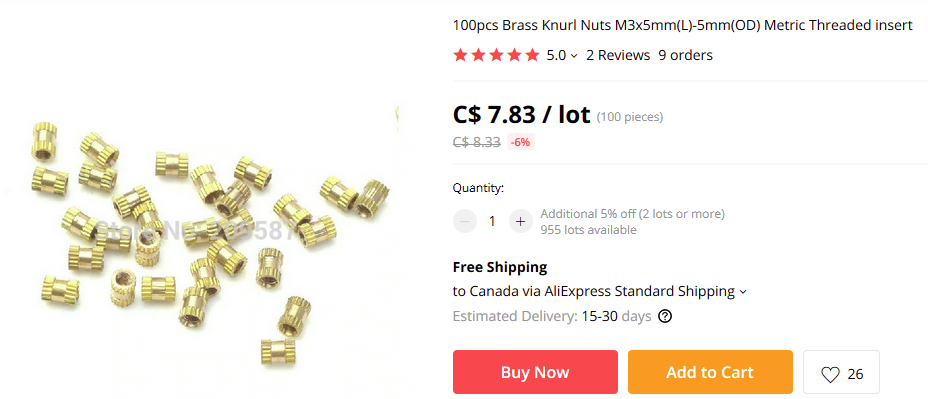

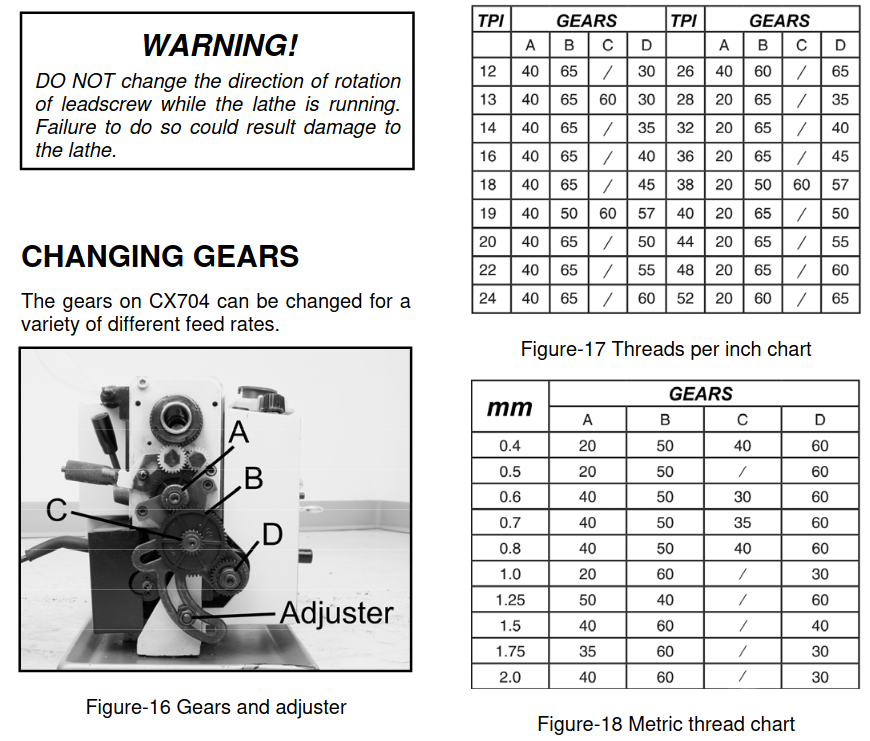

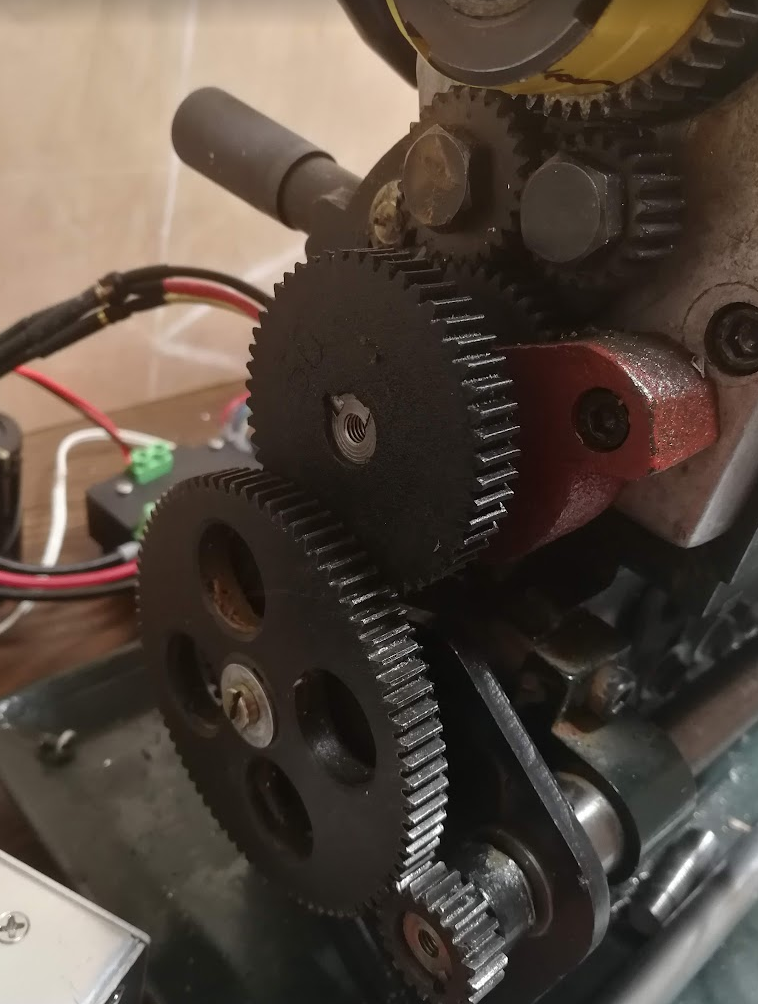

The change gears the lathe came with are steel, which is unusual for a model like this. It came with a set of gears, from A-D: 20/80/20/80. However, this combination isn’t listed on the table anywhere.

The formula is ((A/B)×(C/D))×lead_screw_pitch/initial_ratio

where you have a 3mm lead screw, and it has a 2:1 ratio. So for example, 0.4mm pitch is ((20/50)×(40/60))×3/2 = 0.4.

That means the gears I have are about 0.09mm pitch, which is good as a powered feed, but not intended for any kind of threading.

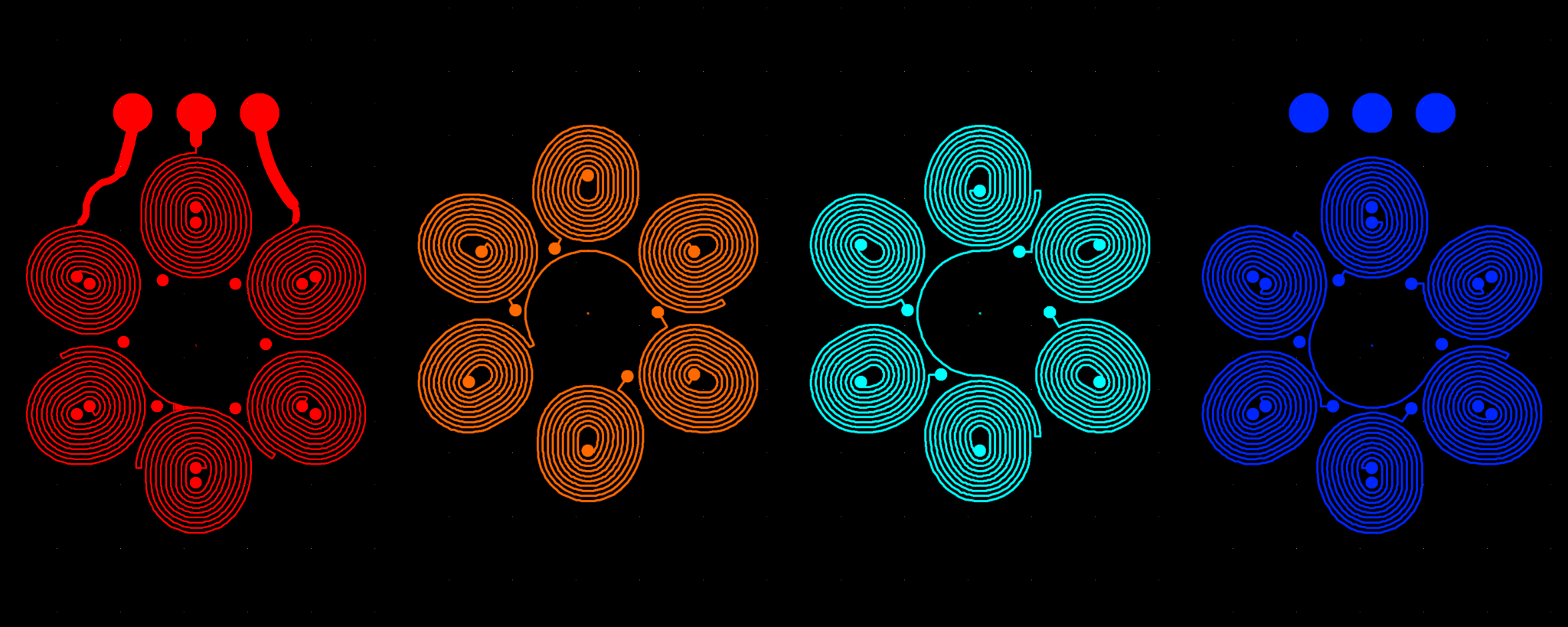

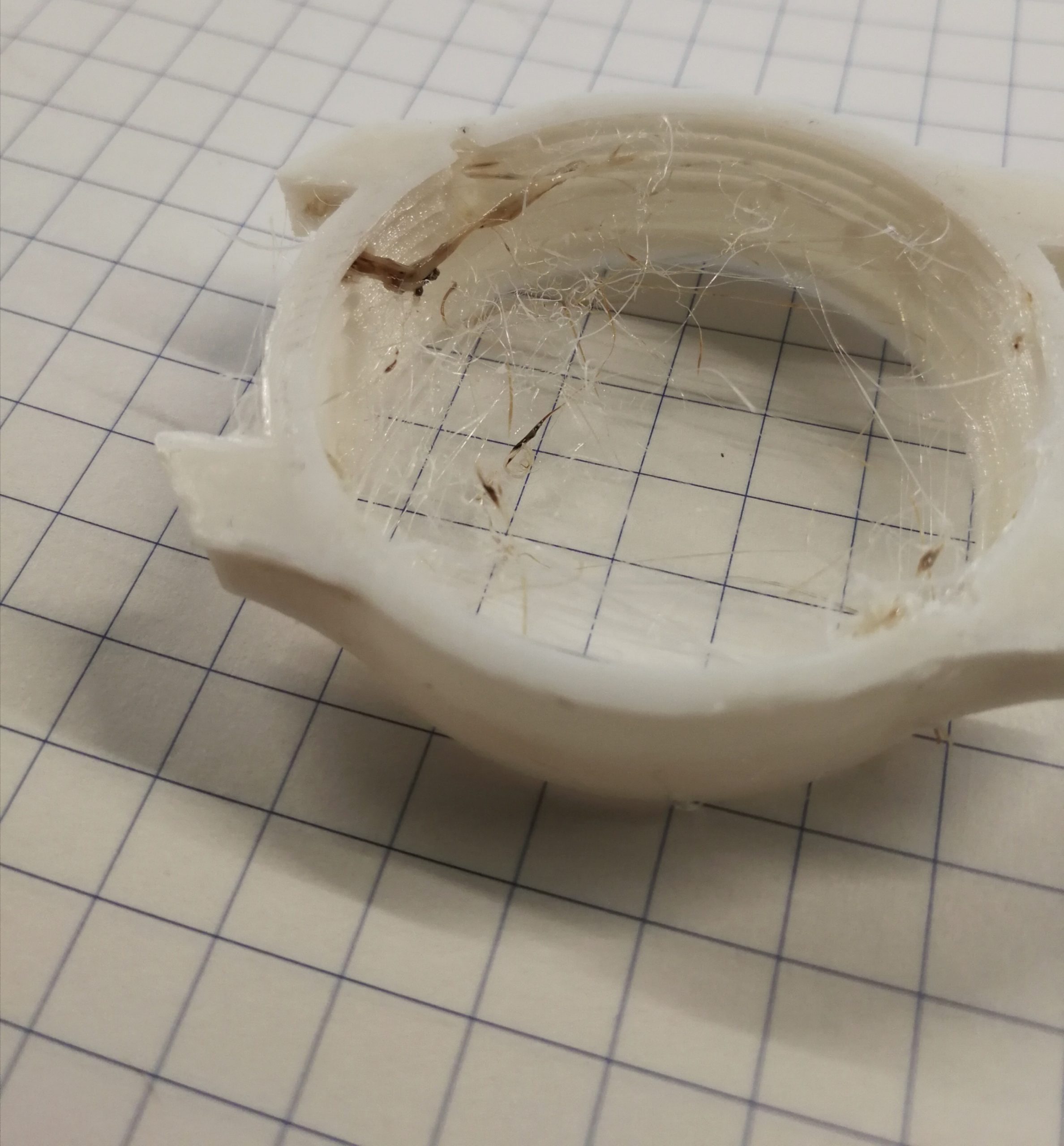

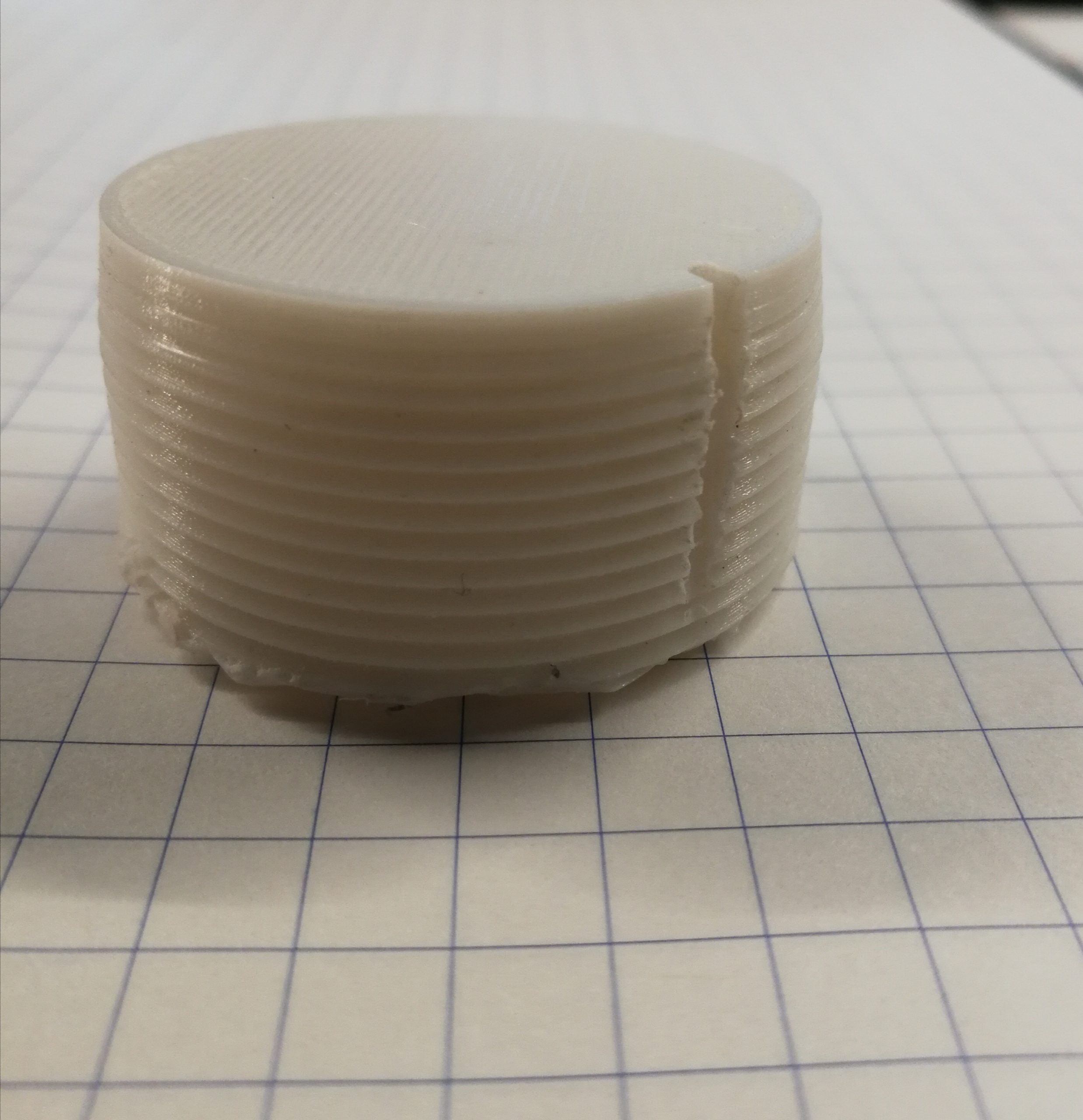

Most of the other examples of this family of lathes use plastic change gears. Obviously using cast or machined nylon, but with a little bit of babying, I bet 3D printed gears would be Good Enough.

As near as I can figure, the change gears dimensions are module 1, with a 20 degree pressure angle. And a thickness of 8mm.

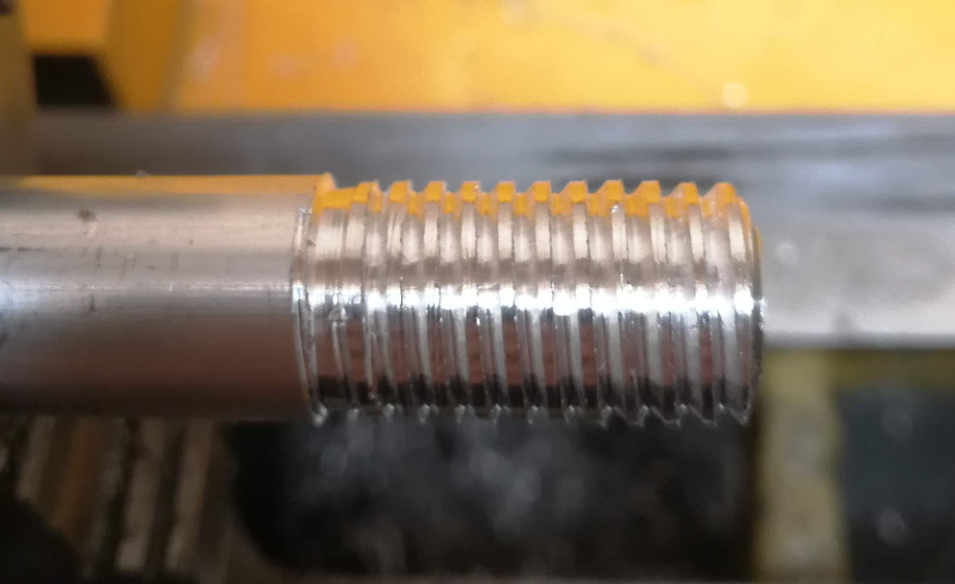

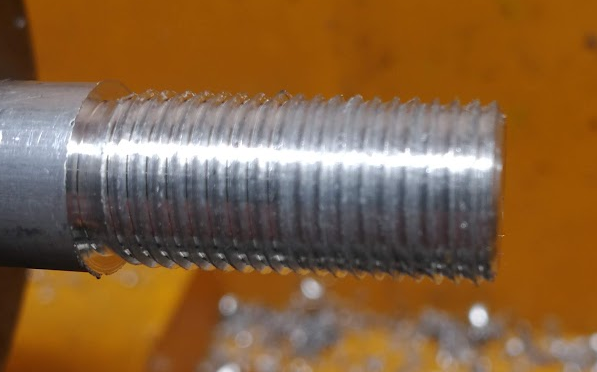

To practice threading, I copied a bolt that I had on hand, which was 1/2″-13 TPI, using the table to get 40/65/60/30.

Looks neat! But my tool geometry is bad and the angles are all wrong, so I reset, bought some more tooling, and moved on to something actually useful.

3D printed change gears work great! I’ve printed off a whole set, and I’m stoked. Arbitrary threads are unlocked.

I wanted to turn a gear shift knob, which has a thread of M12*1.25mm.

Using the formula above, the gears I need are 50/40/40/60.

The outer diameter of the stock is about 11.85mm.

This process ended up being incredibly drama free. Twenty minutes after starting, I had a very-slightly too-loose thread, but it snugged right up when I tightened on the knob.

Success! Now to do some cool things.